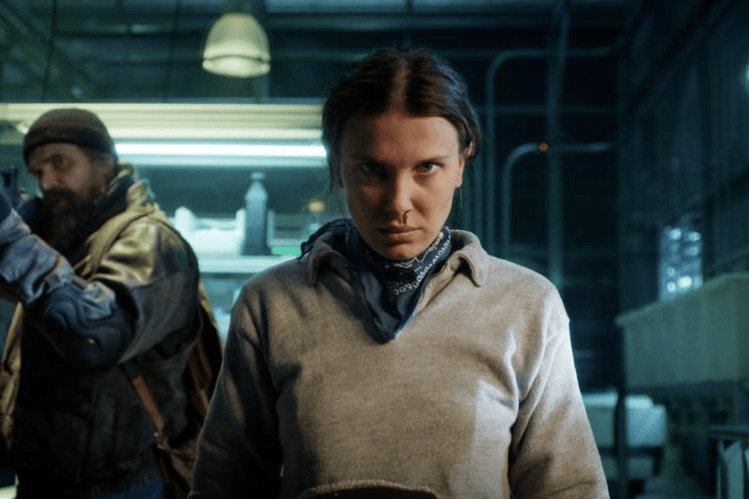

Image Credit: Karyn Kusama, Jennifer’s Body (2009)

Content Disclaimer: Disordered eating, negative body image, weight loss

I was watching television on an American network from abroad one afternoon, when an advertisement for a new brand of GLP-1 agonists interrupted my viewing. GLP-1 agonists belong to a class of drugs intended to treat type 2 diabetes, and have recently been geared towards weight loss. Ozempic is the once-monolithic brand name most popular among GLP-1s, to the point where it has become as synonymous with the generic term as Kleenex is to ‘tissue.’ A-list celebrities from the Kardashians to Oprah Winfrey have been rumoured or confirmed to have used GLP-1s like Ozempic as a way to lose weight quickly, and the trend has reached the mainstream. This became apparent to me as the tagline, “Less hunger. More weight loss.” flashed in bold letters across my screen. I was appalled. As a marketing major, it struck me in more ways than one, the first being the obvious: healthcare companies are advertising disordered eating habits to anyone watching Pluto TV. I had another less political thought, perhaps influenced by my studies – it wasn’t even clever.

The advertisement stuck with me, even through an hour and a half of intermittent gore from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks (1990). For several days, I pondered the political and social implications of diabetes medication co-opted for weight loss and sold to the American masses. Networks in the US are infamous for running advertisements for medications used for any ailment one may have, and before I moved abroad I didn’t know other places were any different. Every ad was the same: a small yet diverse group of actors, a child playing with a dog, and a soft smile from an elderly relative whose life was immeasurably improved by whatever drug was being advertised (besides the suicidal thoughts, nausea, and tuberculosis listed as side effects in the fine print, of course). These ads were always formulaic and transparent; the GLP-1 ads, however, tell another story. They use trendy colours, flashy graphics, Biggest Loser-style side-by-side comparisons of dramatic weight loss, and chic minimalist typefaces to sell to a specific audience: trend-savvy women between the ages of 18-40. The punchline for an ad like this, “Less hunger, more weight loss”, has no need to be clever. It’s straight to the point because it knows its audience. It says, You already want this. Here it is.

To provide some context, the slogan references how GLP-1s work, which is by producing more of a naturally-occurring hormone of the same name that slows digestion. It also regulates blood sugar and helps the body produce more insulin for someone who uses the drug as intended, which seems to have become a sidenote. By slowing digestion, drugs like Ozempic reduce the user’s appetite, which leads to harmful marketing tactics like the advertisement I saw which distracted me from the horrors of Laura Palmer’s cinematic universe. It pointed to something more sinister than perhaps it may seem to a viewer watching in passing: that not eating could be normal, acceptable, and even encouraged; that young women who respond to trend-focused ads may believe that controlling their hunger to lose weight is something even remotely healthy. This kind of thinking leads to disorders like anorexia, bulimia, and an overall destabilised mental condition surrounding one’s body image. Though this issue does not exclusively affect women, we are the main target. The manipulation of women’s health and self-perception is a patriarchal concept, and the marketing of GLP-1s is no exception.

The idea that a woman at any age is expected to fit the beauty standard of having a slim figure is taught from a very young age. Oftentimes it comes from relatives, who were taught the same thing and inflict that subconscious bias upon us. Growing up, this is deemed acceptable by the adults who raise us because we are taught a common misconception that being skinny is equivalent to being healthy. In many cases it’s true, and in just as many it isn’t. Being skinny is not synonymous with being fit – that is, eating healthy, being active, and so on. It can also be a sign of disordered eating habits such as undereating, or even starving oneself. Body Mass Index (BMI) was used as a health indicator when I was younger, up until recent years when it was debunked because it does not account for muscle mass, distribution of fat, or demographics. However, it is now used to determine one’s eligibility for using drugs like Ozempic for weight loss, which was once listed as a side effect in their ads of as little as two years ago when I saw them interrupt screenings of Family Feud. It’s interesting to see that many prescribers of GLP-1s – along with online eligibility checkers – use a benchmark that medical experts deemed misleading over a decade ago and remains disproved (see examples such as a witty piece from a mathematician from NPR in 2009, and a study on its ethical implications done in 2010). Why, then, have so many started serving the Kool-Aid again?

A woman who is skinny from under-eating is easier to control because she is physically weaker. When you starve yourself – medicated or not – you not only lose your ability to defend yourself, but also to operate as normal for daily tasks. You can’t fight an attacker, flee from danger, help yourself or others in an emergency, and you lose part of your cognitive ability to deal with stress because you’re underfueled. You also need help in your everyday life when you lose stamina to walk or bike long distances, are unable to carry anything moderately heavy, and are fatigued more easily than if you would have eaten enough. You can’t do anything on your own – and the use of drugs like Ozempic further magnifies this fact. The common side effects of GLP-1s include flu-like symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and dizziness, along with serious long-term effects like an increased risk of pancreatitis, kidney damage, lowered bone density, and more. This is what is being marketed en masse on networks in the US.

So what’s the upside? Increased self-esteem based on the way others might perceive you? A newfound sense of faux self-confidence, easily shattered by even the slightest implication that how you look doesn’t define you, or worse – that it does, and losing the weight by such drastic means didn’t have the desired effect? As medicated weight loss became more accessible in recent months, the attitude around it began to shift. Tweets speculating the cause of celebrities like Lana Del Rey and Kylie Jenner’s extreme weight loss circulated far and wide, often branded with a new term: ‘Ozempic face.’ The Ozempic face phenomenon was coined as a way of describing a person’s face looking unnaturally hollow or aged – it even reached ABC’s Good Morning America, a popular A.M. news and talk show. Discussion on women’s bodies is rampant, with Twitter users analysing everything down to the size of someone’s feet compared to their legs in an attempt to discern ‘unnatural’ methods of losing weight. The intense media scrutiny along with a look many deem ‘unhealthy’ is the upside of Ozempic – instead of becoming the beauty standard, it seems a popular consensus that Ozempic users look kind of weird.

This reaction is directly related to the accessibility of the drug mentioned above. When Ozempic was exclusively available to celebrities and the ultra-wealthy, it was upper-class. Now that more people across class borders can easily nab a prescription with a BMI calculator, it’s no longer a status symbol. There is a clear stigma around medicated weight loss that has become more apparent in tandem with the rise in popularity: the implication that one cheated, or lost weight the wrong way. Terms like ‘Ozempic face’ are born from this idea. When everyone has a certain privilege, such as having a body type that aligns with the beauty standard, it stops being considered a privilege; however, something must take its place so that the upper echelon can continue having the advantage.

Last year, I came across a video online of a certified pilates instructor with the opening hook, “You are not going to look like Adriana Lima because you do pilates.” It seems counterintuitive when the trend of doing pilates seems to revolve around that goal. The creator went on to say that pilates is about being strong, and that being fit looks different for everyone. When I saw this video, I was going through an episode of intense insecurity about my weight, and it felt like a slap in the face. What do you mean, I don’t get to look like Adriana Lima? It ended up slapping me back into reality.

When models such as Adriana Lima or Gisele Bündchen walked the runway, they were famed for their figures and ability to meet the impossibly strict beauty standard of the 2000s. They were toned, fit, and slim, and their admirability was magnified because this look appeared healthy. Lima is quoted on several occasions referencing a ‘balanced diet’ and frequent exercise, and Bündchen confided in Vogue that a daily dessert – especially with lunch – is a necessity. Both models, famous for their work as Victoria’s Secret Angels, are still hailed as two of the most beautiful and talented models to ever grace the runway. The reason for this, besides their skilled catwalks, is that their looks are inaccessible to most people. A balanced diet and exercise is something many people boast, but many people do not have the same body type or facial structure as Adriana Lima. Perhaps that is Victoria’s Secret: genetics. The beauty of supermodels like Adriana Lima and Gisele Bündchen is revered for its mystery, effortless nature, and unattainability. The utmost privilege is something one cannot buy their way into – it’s something they’re born into. It is not aspirational, nor is it a healthy fixation. The pilates instructor whose thesis I stumbled upon many months ago unknowingly changed my life. I was never going to look like Adriana Lima, and I don’t need to.

The patriarchal foundation of the United States in particular as well as countless other nations teaches women to hate ourselves from what seems like the moment we are born. We are easier to control this way, and the rise in popularity of GLP-1s is a prime example. By implying a beauty standard in their advertisements, a corporation can sell us both self-hatred and the perceived cure for it; however, the cure for self-hatred can never be changing oneself through methods such as weight loss. It must be a reformation of the mind. A common aspect of eating disorders cited by many women who have experience with them is that their ‘goal weight’ to achieve would never be enough to feel satisfied. Promoters of drugs like Ozempic are selling pipe dreams. Extreme weight loss is like an addiction, and the only way to recover is to accept that one deserves to take up space. This notion may not sound revolutionary, yet sometimes it can feel this way; however, it is not impossible. Instead, it is an essential factor in what it means to be liberated.

Leave a comment