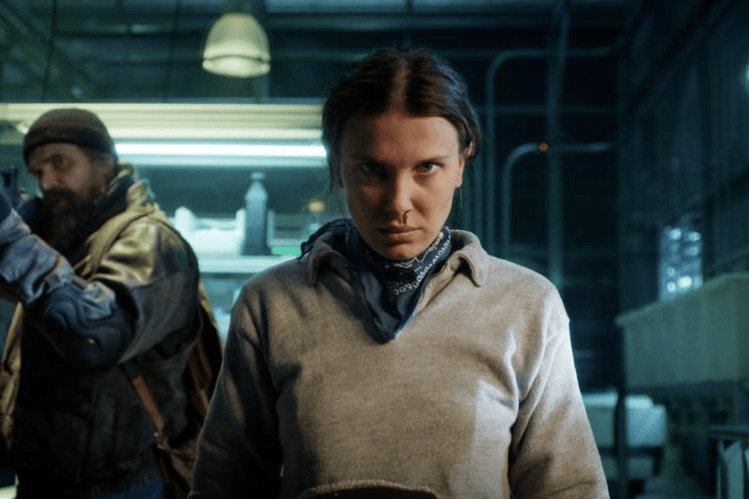

Image Credit: Farefilm.it

Content warning: Rape and assault

This article is part of my series on fictionalised female friendships; I will be using the Bechdel Test and the feminist concept of ‘decentering men’ to guide my analysis and to determine my personal verdict of ‘amazing’, ‘good’, ‘mediocre’ or ‘poor’ representation. To view the introductory entry in the series, click here.

Often hailed as a hallmark in feminist cinema, Ridley Scott’s Thelma and Louise (1991) has galvanised critical conversation since its release. Whilst it has garnered some reproval for its ‘anti-male’ sentiment, I view it as a beautiful and emotionally-charged depiction of female friendship. If you’re unfamiliar with the movie’s premise, it opens with two best friends – the eponymous Thelma and Louise (Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon respectively) – setting out for a weekend vacation in Arkansas. Thelma is initially characterised as a meek housewife whose husband calls the shots in her life, whereas Louise is more assertive and sharp-tongued. From the jump, however, it is established to audiences that Louise brings out a more rebellious, autonomous side in her friend.

Their trip is tragically derailed when Thelma is sexually assaulted outside a roadside bar by a regular named Harlan. When Louise threatens him with a gun, Harlan backs off, but shouts that he should have continued to rape Thelma. Infuriated, Louise fatally shoots him. In the blink of an eye, their lives are turned upside down. They flee the scene, with a singular gun, a haphazard plan of escape and, of course, each other.

With the women’s flight from the law as well as the movie’s thematic preoccupation with justice and liberation, Thelma and Louise echoes several genre markers of the ‘Western’. This classic American genre typically features an array of familiar male stock characters, from sheriffs and vigilantes to outlaws and rambunctious cowboys. In his appropriation of this recognisable American form, Ridley Scott subverts a stereotypically androcentric genre and restructures the gender roles associated with it.

Image Credit: IMDb

In terms of the Bechdel Test, Thelma and Louise passes with flying colours. The two women are strongly written characters who discuss work, the justice system, questions of female liberation and their invaluable friendship. While the test isn’t a catch-all measure of positive female representation or feminist messaging, it is a useful means of dissecting whether a film focuses more on women’s experiences over men’s.

Laura Mulvey’s seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975) outlines that mainstream cinema traditionally focuses on masculine, heterosexual perspectives. She suggests that female characters merely serve as passive objects or ‘spectacles’ to satiate the male gaze. Unlike male characters, women on screen rarely move the plot forward or possess any sense of agency. As mentioned, Westerns are an overtly male-centric genre , with women often being characterised as weak counterparts to men or voyeuristically portrayed as seductresses. However, in the case of Thelma and Louise, the eponymous protagonists are always the central focus.

In their essay “Gender, Genre, and Myth in “Thelma and Louise”” (1993), Glenn Mann argues that “What the narration of Thelma and Louise attempts to do … is to inscribe both women as subjects and agents of the narrative, give authentic voice to their desires, and mute the discourses of the male characters.”(39) Upon the film’s release, female audiences found the duo as women they could root for and relate to, with men simply functioning as peripheral entities in the diegesis. Male characters are secondary to the narrative, often serving as obstacles or threats. Even Brad Pitt’s character – who is momentarily figured as a romantic interest for Thelma – is quickly discarded from the storyline after he robs the protagonists. He is objectified by Thelma and gives her a new outlook on sexual liberation and pleasure, flipping the script on stereotypical portrayals of heterosexual romances on screen. Thelma and Louise function as agents within their own story, whereas men are subject to shallow characterisation and subdued parts within the wider narrative. By challenging Mulvey’s observations on cinema, Ridley Scott – and the powerful performances of Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon– dismantles the traditional male lens through which we are often forced to perceive visual media.

Image credit: IMDb

Thelma and Louise both grow and evolve as characters, but their journey to self-actualisation stems from platonic love and solidarity rather than any sort of romantic connection. Thelma is inspired by Louise’s decisive and assertive character; she grows more strong-willed, detaching herself from her prior domestic responsibilities and submission to her husband. For example, in a brave act of defiance that completely opposes her initial character, she robs a store-owner at gunpoint midway through the film. Their bond deepens outside of male-centered environments and discussions, but they also showcase dazzling displays of solidarity when faced with masculine threats or adversity. The most obvious scene that comes to mind is Louise shooting Harlan, but I also love the scene in which they blow up a truck driver’s vehicle as revenge for his demeaning comments and crude gestures towards them.

Obviously I couldn’t finish this article without discussing the film’s iconic ending. When the FBI finally track the pair down, they refuse to surrender. They kiss and hold hands, before accelerating off a cliff to their presumed deaths. This shocking conclusion represents an ultimate act of liberation and solidarity against the male forces that have constrained them. Thelma and Louise end the cat-and-mouse chase with the police on their own terms and, most importantly, they do it together.

My verdict: Amazing representation

Leave a comment