Image Credit: Amy Miller

For a young girl, the summer holidays are a dream: six weeks free from academic pressure, which my childhood self would spend infatuated with sea and sand, immersed in novel after novel. But as I age, this sense of freedom seems to dwindle. I have no essays to write, no lectures to attend, no grades to maintain, and yet I feel trapped. In speaking to my friends and fellow university students I have learned that I am not alone – and this collective experience of summer as purgatory is one I feel the need to unpack.

This summer is my second as a student, and it’s therefore my second time moving home after a long academic year. At first the move is a kind of relief, an escape from the chaos of exam season to the familiarity of home comforts. But, like everything, comfort comes at a cost.

Unfortunately, the annual return home is not only a geographical shift. Each June, I am forcibly transported back into the body of an old, flawed, ostensibly lost self; that is, myself at seventeen years old. In close-quarters with my mother, I am once again a surly, argumentative child lacking in patience and empathy. It’s not that clear cut, of course. I do not turn evil the second I step off the train – rather, the now unfamiliar sight of my small town and even smaller bedroom strikes a deeply uncomfortable chord. I am used to the independence of student life, during which I do not report my whereabouts to my parents. To be asked – undoubtedly out of nothing but love – who I am seeing and when I will be home has begun to evoke feelings of injustice and ridicule, feelings which do nothing but force me to question my age. 20 years old and asking my mum for a lift into town? That can’t be right.

This question of lifts is another complication of the return home. During term-time, living in York means constant access to public transport or taxi services and, failing that, a relatively walkable place to call home. On the other hand, hailing from a small town in North Devon means my summers look quite different. As someone who has yet to learn to drive, my ability to go out of an evening tends to hinge on the generosity of those who can, friends and family alike; while I am lucky enough to live only half an hour from the high street, I am also a young woman uncomfortable walking home in the dark – with good reason, I think.

The inconvenience of youth in a small town does not stop at transport and is only further entrenched by the complete lack of age-appropriate venues. My home town, for example, boasts a total of one nightclub, which I have not been able to stomach since 2023. Even so, having been blessed with a disco Wetherspoons we tend to make the nights our own – but this is to be shut down over the next few months, having lacked foot-traffic among the aging population all year. A summer full of returning students is simply not enough to keep the ball rolling, meaning the local entertainment cannot cater to us.

Past petty boredom and teenage reversion there comes another strange adjustment: the complete absence of an enforced routine. I may not always embrace it, but the university timetable certainly works wonders for my productivity levels and, consequently, my sense of fulfilment. Knowing I need to be in a certain place at a certain time, even if it happens to be the furthest corner of campus at 9am, gives me a tangible purpose that is simply not replicated at home. Because I work from home as a tutor, my hours are split: I am of course grateful for the job’s flexibility, but it does not help redirect my faltering awareness of time and its passage.

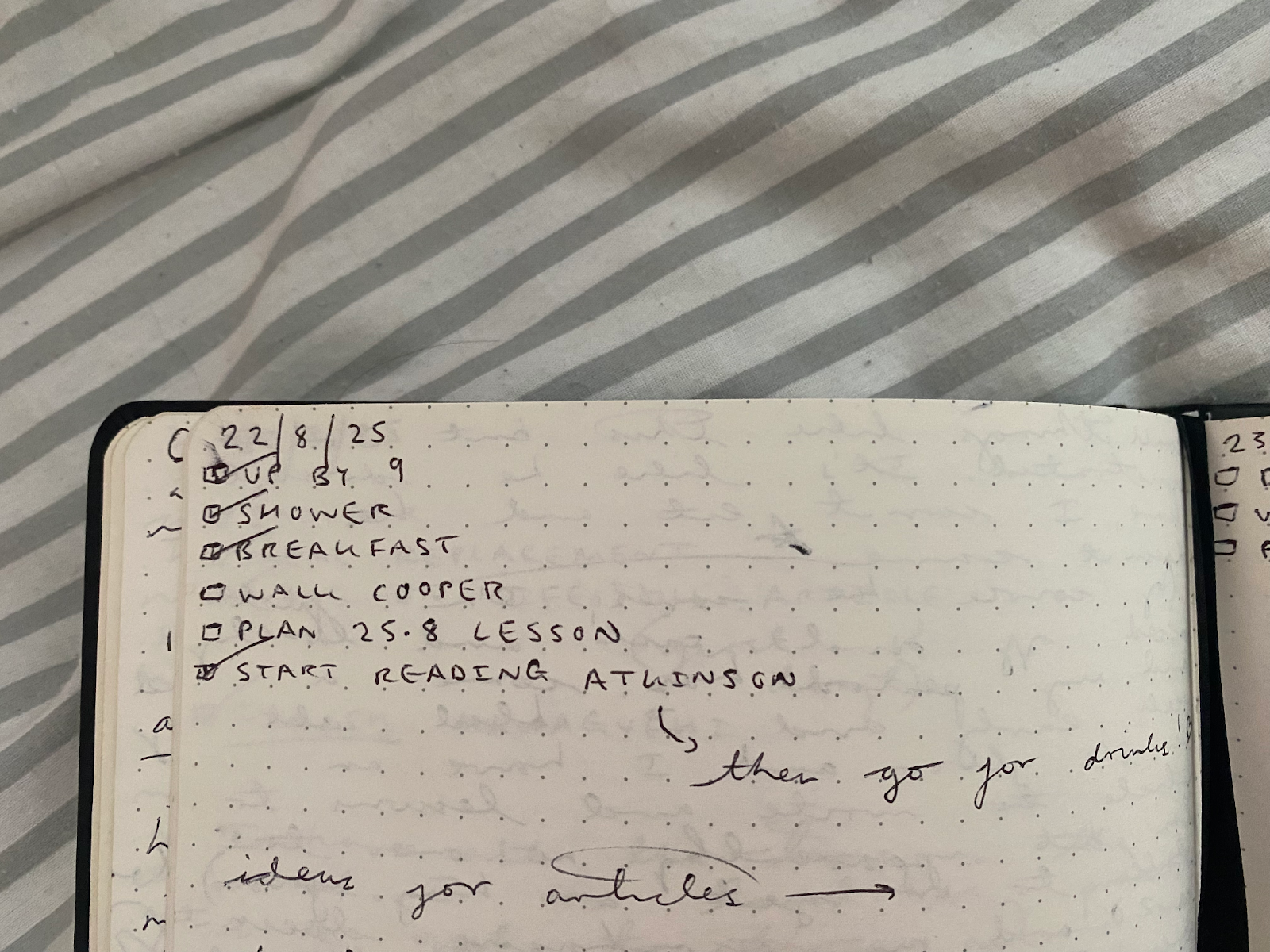

All of this to say – being home for the summer is hard. But what can we do to make it easier? First and foremost, we must appreciate the home we are given. It is a privilege to write this article, to complain about parental power dynamics and irregular buses, in a world with so many begging for just a roof. We must never forget this, even in our strongest moments of lamentation. On a day-to-day basis, though, I find that the creation of and adherence to one’s own routine is the best way to overcome all these complicated feelings. Each night I write tomorrow’s to-do list, which consists of everything I have planned, from my morning walk to the lessons I must plan or teach that day. It is meticulous – my journal often resembles the daily log of a primary school child – but it works. Everything becomes a goal to be checked off and moved past, my ultimate aim being to complete the list by sundown.

An example of my daily lists

Some people have told me that my perpetual checklists take the fun out of the day; I could not disagree more. Even if this exact technique does not appeal to you, I believe the key to both enjoying your time and spending it wisely is to organise it. Each day presents an opportunity, not necessarily for academic or economic productivity, but for enjoyment. I believe we should take this in our stride, and that we must not let homely comfort force us into boredom. Keeping track of my fulfilment and the small ways in which it manifests allows me to claim control over my daily life, and this autonomy is essential in a journey towards contentment.

You heard it here first: take control of your summer, or it will control you!

Leave a comment