Image Credit: Evelyn Barnes

Gossip. The word alone conjures images of whispering women, scandalous secrets, and moral finger-wagging. Defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as “conversations or reports about other people’s private lives that might be unkind, disapproving, or not true”, gossip is often framed as petty, malicious, and distinctly feminine-coded, morally discouraged by adages like “don’t tell tales” or “if you don’t have anything nice to say…”.

But what if we’ve been getting it wrong?

Yes, gossip can be cruel. When misused, it spreads unsolicited opinions and reputational damage like wildfire. I’m not here to rebrand malicious rumour-mongering as feminist rebellion. That’s not empowerment – it’s just mean. But brushing all gossip off as toxic misses the point. Gossip isn’t just idle chatter; it’s a form of strategic, moral, and communal communication. When we trace its history, particularly through the lens of gender and power, it becomes clear that gossip is not the problem. Silencing it is.

Social Glue (and Grit)

Gossip has long operated as an informal justice system. It regulates behaviour, reinforces community norms, and circulates warnings when formal structures fail. Think whisper networks that protect employees from abusive managers, or group chats that share intel on landlords, professors, or peers. In these cases, gossip isn’t malicious; it’s protective. It’s the social glue that holds communities together, and sometimes the grit that keeps them truthful.

Queer Communities – the Intersectionality of Gossip

Not all gossip travels the same path or carries the same weight. To understand its full moral and political complexity, we must examine gossip through an intersectional lens. Coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality highlights how overlapping systems of oppression, such as racism, sexism, classism, and ableism, shape people’s lives differently.

For many marginalised groups, gossip has never been “just talk”. It’s an alternative mode of information-sharing, solidarity, and protection, especially when formal structures like HR departments, the police, or the media refuse to listen, or actively cause harm.

Think of black women in white-dominated workplaces trading quiet warnings about racial microaggressions, or trans and queer communities sharing lists of safe clinics, allies, or dangerous organisations. These aren’t petty whispers. They’re lifelines. When the official narrative silences or gaslights, gossip becomes a parallel network of truth-telling.

In these contexts, gossip is not idle; it’s urgent. It becomes the informal infrastructure of resistance, warning, and survival, particularly for those who are most often denied credibility in public discourse.

Is Gossip Harmful? And if so, how?

While rumours are often defined as unverified talk, gossip gives these rumours legs. And when unverified information is passed off as fact, it edges into fake news. But reducing gossip to misinformation ignores its role in resistance. Throughout history, controlling gossip has often been a form of censorship, especially of women’s speech.

Parlour Rooms, Pub Bathrooms, and the Politics of ‘Babble’

Image Credit: The Regency Era (website)

Historically, women’s conversations have been dismissed as inferior to men’s networking. From the parlour and salon rooms of the 16th and 19th centuries, spaces where women gathered to exchange ideas, to the modern ritual of pub bathroom solidarity, women’s speech has often been trivialised rather than recognised as powerful.

Parlour rooms weren’t just for embroidery and tea; they were sites of intellectual and political exchange. As Goodman notes, these gatherings transformed the “literary public sphere into a political one”, allowing women’s voices to transcend domestic boundaries. But this power didn’t go unnoticed. In 1547, a proclamation in England forbade women from gathering to “babble and talk”, instructing husbands to keep their wives at home.

Fast forward to 2024, and the Taliban’s latest law takes this silencing to dystopian extremes. Women in Afghanistan are now banned from speaking in public, even from within their own homes. Laid out in a 114-page document titled Rules for Preventing Vice and Promoting Virtue, the law criminalises female voice in all forms: speech, prayer, and song. As reported by the BBC, even taxi drivers can be punished for transporting women without male guardians, and women are forbidden from making eye contact with men they are not related to.

This isn’t just repression, it’s erasure. And in such contexts, gossip becomes more than talk. It becomes resistance.

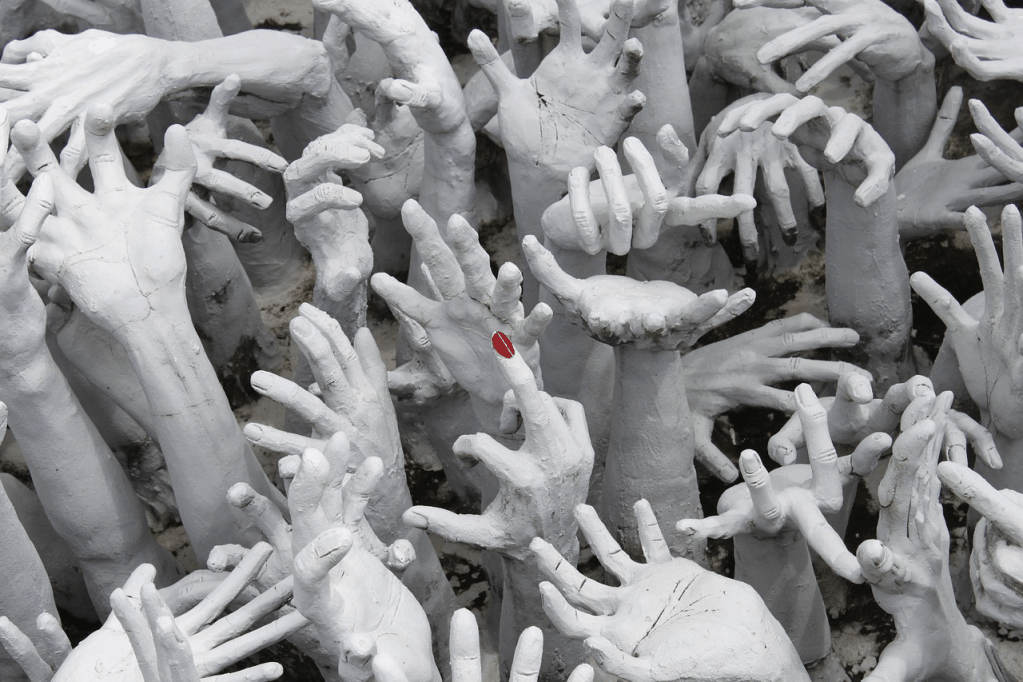

Image Credit: Pixabay

Whispers and Weapons: Gilead and the Gospel of Gossip

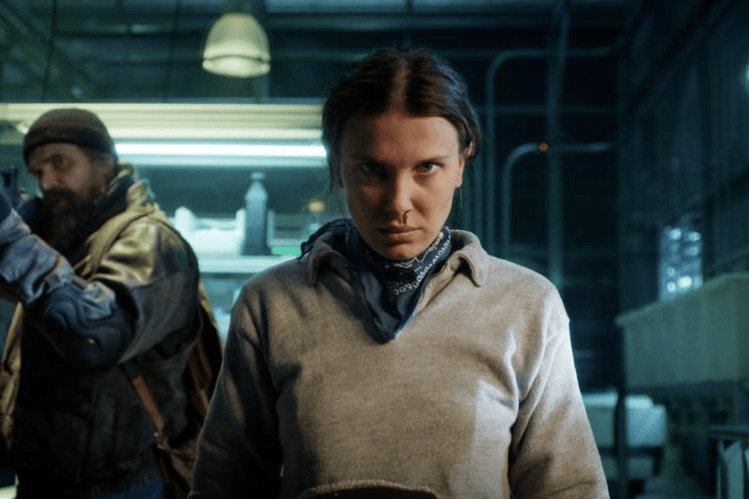

If the Taliban weaponises silence, The Handmaid’s Tale turns whispering into resistance. Margaret Atwood’s 1985 speculative fiction novel imagines Gilead, a regime where women are reduced to wombs on legs and where small talk is practically treason.

“Nothing changes instantaneously”, Atwood writes. “In a gradually heating bathtub, you’d be boiled to death before you knew it”. Every act of rebellion in the novel is slow, coded, and dangerous. The Handmaids trade gossip like contraband: scraps of scandal, secret warnings, rumours about Commanders and their sins. Even silence becomes suspicious. A raised eyebrow is revolutionary.

Feminist scholar Deborah Tannen once said, “For women, talk is the glue that holds relationships together”. In Gilead, that glue becomes a weapon; sticky, subversive, and impossible to scrub away. Gossip becomes the only news bulletin in a regime that punishes the truth.

From Parlour to Platform: Gossip in the Digital Age

What once happened in parlour rooms now unfolds in private group chats, anonymous forums, and comment sections. Technology hasn’t killed gossip; it has supercharged it.

In digital spaces, gossip becomes faster, more visible, and more unpredictable. Group chats become the new whisper networks. On platforms like TikTok, X or Reddit, anonymous users share stories of harassment, dysfunctional or unhealthy relationships, toxic bosses, or problematic influencers.

At its best, digital gossip is a form of decentralised justice. It bypasses gatekeepers, amplifies unheard voices, and protects vulnerable people who might otherwise remain silent.

But digital amplification cuts both ways. Gossip can morph into misinformation, or worse: public shaming without due process. The virality of social media means a single rumour can destroy reputations overnight, especially when the nuance of intent or context is lost. And while marginalised people use gossip as a shield, they are also disproportionately harmed when the crowd turns against them.

Conclusion: Gossip as Moral Navigation

If gossip is inherently wrong, why is it so universal and, at some moments, even necessary? The answer may lie in its deeper functions. Gossip is not just idle talk; it’s a way of knowing, connecting, and surviving. It reflects the intricate realities of human relationships, social accountability, and ethics. Rather than shaming gossip, we should ask: what truths does it carry? In a world where official channels often fail the most vulnerable, gossip doesn’t just survive, but protects; it warns, and sometimes, it revolts. The next time someone says, “Don’t gossip”, perhaps the better question is: Whose silence does that serve?

Leave a comment