Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Content warning: contains references to abuse and sexual harassment.

In the summer of 2022, anyone could watch the Johnny Depp vs. Amber Heard trial online at home, through the livestream or the frenzy of clips circulating social media. For most people it was the latter.

Dubbed the first ever “trial by TikTok,” the BBC reported how “There have been essentially two cases here – one decided by a jury and another by the public.”

In online spaces, support for Depp was overwhelming, whereas Heard was torn apart. What concerned me, and many women, was how Heard wasn’t merely criticised or having her accusations analysed, she was slandered and humiliated online for everything – her manner of speaking, the way she conducted herself, and her facial expressions were all clipped, impersonated and mocked. Her deeply serious accusations and the trial in which she had to relive her trauma were turned into a public spectacle and it seemed people were unwilling to hear her out.

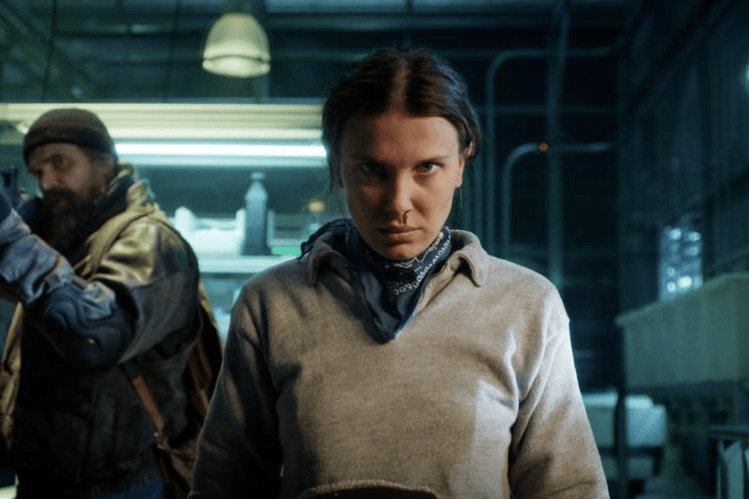

Depp vs Heard seemed like an irreproducible frenzy, until, years later, the internet became obsessed with the It Ends With Us controversy – what started as rumours of creative and personal clashes on set, turned more sinister when Blake Lively alleged Justin Baldoni (the director and Lively’s co-lead) sexually harassed her and created an uncomfortable working environment. What followed was a public wave of hatred for Lively, attacking both her character and appearance, throwing labels of “bitchy”, “difficult” and “mean girl” at her. Hence, her allegations against Baldoni were largely and publicly discredited as a consequence of the online hatred.

If you’re thinking this is all too familiar, unfortunately the similarities don’t end there. According to the BBC, Baldoni hired the same PR crisis manager used by Johnny Depp.

The online smear campaign against Lively was not incidental or organic – it was very deliberately orchestrated to discredit her. In exposed texts from Baldoni to his PR team, he had sent a Twitter thread attacking another contentious female celebrity, Hailey Bieber. The thread collected out-of-context examples over the years of her “bullying women,” creating the impression that Bieber is a “mean girl.” He tells the team “this is what we would need” to do to Lively – to turn the public against her through online attacks on her past actions, her personality and her character.

Once history repeats itself, we must question if these are isolated incidents, or if there is a pattern. I would argue that these are systemic attacks from the PR machine used to discredit and silence women and victims of abuse. Examining how these two smear campaigns overlap exposes the implications of being a woman in the public eye. I contend that for women, it is not enough to speak honestly, you must be perfect beyond question to be believed.

The myth of the ‘perfect victim’ problematises coming forward about abuse as a famous woman. Reductive stereotypes about gender often envision women as innocent helpless victims, so when we see anything more complicated or nuanced than this, it makes us uncomfortable. Misogyny is so entrenched in society that we act as though women must be perfect, moral beyond reproach and, crucially, likeable as people (a metric which is distinctly harder for famous women to achieve than famous men), to be believed and to not be mocked or ruined for coming forward. This is echoed in how people will advocate for women who come forward, until the woman is someone they don’t like or who doesn’t fit their ideal of female victimhood.

This is what makes both these cases so uncomfortable. It is one thing to see a woman criticised fairly for her actions, but it is entirely different to watch women be reduced to sexist stereotypes when they accuse powerful men of abuse. In such complicated and nuanced cases, where accusations are being aimed at both sides, why are the men spoken about fairly, whereas the women are mocked?

Ad hominem attacks were wielded against Heard and Lively online and whether we realised or not, these were an incredibly deliberate and targeted smear campaign against them. We live our entire lives online, our curated social media feeds heavily influence our opinions, therefore having your phone littered with posts highlighting the women’s every flaw makes us less likely to credit their voices. You might have negative opinions on how Lively spoke to another woman in an interview several years ago, or how her hair looks, or how funny that skit mocking Heard’s facial expressions on your TikTok was, and having these opinions is fine. But we must identify that these characteristics are not pertinent to the truth of their claims. We must separate likeability from our judgements when it comes to matters of abuse, assault and harassment, as likeability is a far too gendered metric.

Our double standards of who we believe also emerge when the man accused is a ‘likeable’ or beloved figure, which certainly applies in the case of Depp. As a beloved actor who many people grew up with in roles in the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise or numerous Tim Burton films, many people already had a strong parasocial attachment to him before the allegations emerged. Therefore, they felt indignant at the accusations that didn’t fit their idealised preconceptions of him, and hence felt contempt towards Heard from the beginning.

Men are often infantalised online in these smear campaigns, so we feel a sense of protectiveness over them and view them as more innocent, and the parasocial obsession with them only increases. During the Depp vs Heard trial, numerous TikToks clipped him speaking in court with sentimental music played over it and compilations of his “funniest moments in court” were created on YouTube. Spectators also highlighted Heard’s “fake crying” and moments where she appeared to be over-acting. All of these curated clips we see through social media cultivate our opinions of these celebrities and feed our biases. Not to mention Depp was one of the most famous male celebrities in the world, whereas Heard had much less of a platform – she was also only in her early 20s when she met him, and he was in his mid-40s.

The site of these smear campaigns has been social media, which has unique functions that PR teams can exploit. An example is thumbnails typically using unflattering photos of Heard or Lively, painting them as unpleasant, or angry or emotional, whilst the men involved have more flattering photos selected. Outreach itself can be biased – Buzzfeed reported that TikToks with #JusticeForAmberHeard garnered views in the millions, whereas #JusticeForJohnnyDepp garnered up to 5 billion.

Additionally, on social media we see content and clips which have been curated and recycled and impersonated, until eventually we see the people involved as characters whose drama we can enjoy and consume, and we forget that there are real people on the other side of the screens we view this from. It’s dehumanising. Regardless of who you believe, it’s dehumanising to have the most intimate and traumatic moments of your life turned into tweets, TikToks, hashtags, skits. Whether or not you like the women involved, we cannot sink to the level of contempt for women that makes us believe they deserve this.

While Lively’s reputation has certainly taken a massive hit since the It Ends With Us controversy, with her money, resources and allies with large platforms, she’s been able to fight back against Baldoni and his PR team to an extent. In the leaked texts between Baldoni’s team, they threaten “we can bury anyone.” Hauntingly, they were right – Lively’s reputation has certainly been damaged with ease, and Heard has almost entirely left the public eye, with only a couple of acting credits since the trial. In an interview with NBC News, the interviewer pointed out to Heard that no other women have alleged any abuse from Johnny Depp. Heard simply asks: “Look what happened to me when I came forward. Would you?”

We must implore ourselves to recognise signs of a smear campaign against women in the spotlight, the attempts to discredit them, and recognise this cycle before it repeats itself, before another victim of abuse or harassment is buried. We must recognise ad hominem attacks and remind ourselves we don’t need to like a woman to believe them and identify when misogyny is used against them. Not only for the sake of these women, but for the sake of any victim of abuse and misogyny, famous or not – these attacks make women feel unable to speak up as they can so easily be humiliated, reputationally ruined and have their trauma turned into a spectacle.

Leave a comment