Image Credit: Pixabay

The St George’s Cross is everywhere. Hung from lamp posts, painted on roundabouts, and waved at matches. But what does it mean to fly the English flag today? For some, it’s a symbol of pride. For others, it’s a warning.

Here’s the irony: the flag itself is borrowed. Like so much of English culture, it’s stitched together from other places: adopted and rebranded. From the Caryatids to curry on every high street, England’s identity is a mosaic of cultural imports. In tracing the flag’s tangled journey from foreign saint to nationalist emblem, I ask: who gets to claim Englishness?

Image Credit: Pixabay

The Original Meaning of the Flag and the Man Behind It

Saint George was neither English nor British. Rather, he was born between 275 and 285 AD in Cappadocia, now part of Turkey. His father, Saint Gerontios, served as an official in the Roman army, with his mother, Saint Polychronia, being from modern-day Palestine. Imprisoned for his Christian beliefs, George was executed on the 23rd of April, a day we now commemorate as St George’s Day. His official adoption as a martyred saint came in the 14th century, when King Edward III founded the Order of the Garter in his name.

St George is also the patron saint of many other countries, including Greece, Portugal, Ethiopia, and Palestine; hardly a figure exclusive to English heritage. But in medieval England, the Church needed a national symbol that wasn’t a monarch or political figure. St George, with his dragon-slaying myth and warrior aura, fit the bill.

However, the image we associate with him today, the knight on a white horse, slaying dragons, emerged centuries later.

We’ve always been cultural magpies: borrowing saints, symbols, spices, and stories. In that sense, Englishness isn’t so different from The Borrowers, the classic children’s tale where tiny people live by quietly repurposing the things others leave behind. But unlike The Borrowers, our national borrowing hasn’t always been quiet, and seldom innocent. The red cross wasn’t English either; it originated in Genoa, Italy, and English ships reportedly “rented” it to borrow Genoa’s naval clout and prestige. The irony is that a flag stitched from foreign threads is now used to gatekeep national belonging. The fact that both the saint and the symbol were imported complicates any claim to the flag as a purely English creation. Yet, this nuance is rarely acknowledged by those who use the flag as a symbol of exclusion and a boundary marker, a test of who counts as ‘truly’ English.

Image Credit: Evelyn Barnes

Museum of British Values (Entry £0, Exit £££)

If we can claim a flag and a saint from other cultures, what does that say about our own?

But the flag’s power doesn’t come solely from its historical palimpsest. It’s also shaped by institutions where the national identity is taught, curated, and legislated.

National symbols aren’t just waved in the street; they’re embedded in classrooms, galleries, and political speeches. The school curriculum in England often glosses over the violence of the British Empire, presenting colonialism as a civilising mission. Politicians invoke “British values” as a moral compass, yet rarely define them beyond vague appeals to tradition.

Museums and heritage sites frequently frame national history through a lens of triumph and continuity, sidelining dissenting voices. Only one per cent of the artefacts in the British Museum are actually British; a quiet testament to imperial plunder masquerading as cultural diversity.

Meanwhile, the media and politicians play a key role in creating and fostering a racist culture within the UK, one in which discrimination is permissible. In parliamentary debates and tabloid headlines, negative terms like ‘illegal’, ‘flood’ and ‘influx’ are persistently used in association with migrants, posing them as a threat to white British nationals. The word ‘illegal’ ranks among the top five most strongly associated with migrants — a linguistic cue that frames them as threats rather than neighbours.

Flagged for Division: The EDL and Tommy Robinson

After the Second World War and the decline of the British Empire, the meaning of the St George’s Cross began to shift, and it crept back into use, first through its use by right-wing groups and, more recently, through sports fans.

In the late 20th century, far-right groups, the British National Party (BNP) and the English Defence League (EDL), seized the flag as a rallying point. It appeared on placards at anti-immigration marches, in football terraces steeped in hooliganism, and in online spaces. The flag became a symbol of division, erasing the contributions of migrants, minorities, and anyone outside the imagined mould.

Tommy Robinson’s EDL wrapped itself in the St George’s Cross while marching through multicultural towns with chants of “taking our country back.” Germany’s Pegida, the far-right group Robinson collaborated with, borrowed the same playbook: flags, fear, and football chants. When Pegida’s founder was caught posing as Hitler on Facebook, the mask slipped, revealing the extremism beneath the patriotism.

As political scientist Dr Matthew Godwin notes, far-right movements often weaponise national symbols to construct a mythic narrative of cultural purity. The St George’s Cross is now being manipulated as a shorthand vision for an exclusionary vision of England.

That vision resurfaced in 2025 with Operation Raise the Colours, a campaign that encouraged mass displays of the St George’s Cross across the UK. Supporters tied flags to lampposts, painted them onto roundabouts, and draped them from council buildings, with the campaign’s slogan being ‘A grassroots movement for unity and patriotism’. But the campaign’s roots were far from neutral. It was co-founded by Andrew Currien, a figure with ties to Britain First and the EDL, and quickly gained traction among right-wing influencers and MPs.

The movement began in Birmingham. It quickly spread throughout the West Midlands, where my home county, Staffordshire, sits. Over August, flags were erected in my small hometown, splayed across nearly every lamppost, painted onto roundabouts, draped like costumes over the bones of familiar streets. It was a chilling sight. Not festive, but foreboding.

This sounds negative considering the claims of the campaign, but these weren’t calls to celebrate Britishness. They felt more like territorial markers—symbols not of unity, but of exclusion. What’s meant to be a shared emblem had become a performance of belonging, staged for some and staged against others. I wasn’t alone in feeling unsettled. For many, the sudden saturation of flags felt less like a celebration and more like a takeover.

But this behaviour was reflected in white MPs: Shadow Lord Chancellor Robert Jenrick posted a photo of himself climbing a lamppost to hang a Union Jack, declaring, “While Britain-hating councils take down our own flags, we raise them.” The rhetoric echoed Trump-style populism, framing flag removal as an attack on national identity. But in places like Tower Hamlets, Birmingham, and Durham, councils removed flags from public infrastructure, citing safety concerns and rising tensions. Anti-racist groups condemned the campaign as a thinly veiled attempt to intimidate migrants and stir division.

Even Prime Minister Keir Starmer, while affirming his support for national symbols, warned that flags can be “devalued” when used to provoke rather than unite. Once again, the St George’s Cross was caught between pride and provocation — between celebration and control.

Image Credit: Pixabay

Nationalism Isn’t Just British

National symbols are used to exclude across borders, and England is far from alone. In France, the secular principle of laïcité has been central to national identity since the early 20th century. Laïcité was meant to separate religion from the state. Today, it’s used to justify laws that disproportionately target Muslim communities. The 2004 law banning conspicuous religious symbols in schools, including headscarves, and the 2010 ban on full-face veils in public spaces were framed as measures of neutrality and public safety. Yet these laws restrict religious freedom and reinforce the marginalisation of Muslim women, turning secularism into a tool of cultural policing.

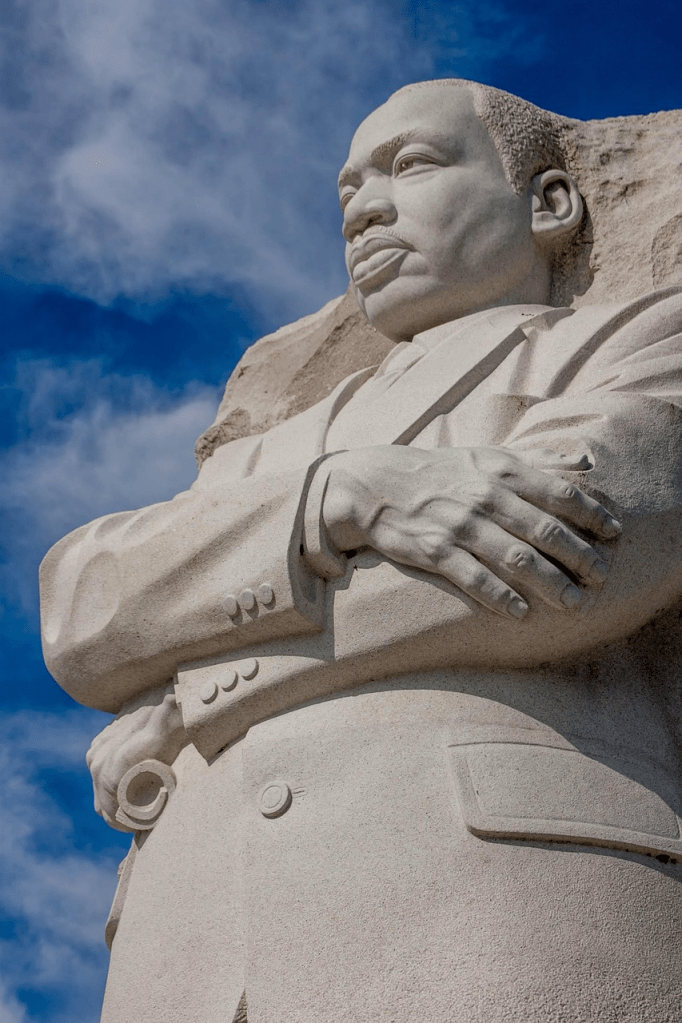

In the United States of America, the US flag has long been a site of contention. It’s a banner of protest and a banner of oppression, often at the same time. During the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. and other activists marched beneath it, demanding that America live up to its promises of liberty and justice. But the same flag has also flown at white supremacist rallies, including Charlottesville in 2017, where it appeared alongside Confederate and Nazi symbols. After 9/11, flag displays surged, often accompanied by anti-Muslim rhetoric and surveillance policies. For some, the flag represents freedom; for others, it signals a nationalism that has historically excluded Black Americans, Indigenous peoples, immigrants, and religious minorities. A flag’s meaning is not fixed; instead, it shifts, somewhat dramatically, depending on who is waving it and what vision of the nation they’re defending.

Understanding and Reclaiming the Symbol

So how can we shift the St George flag’s meaning to be one of unity?

While far-right groups have used the St George’s Cross to signal exclusion, others are reclaiming it as a symbol of inclusivity. Anti-racist football fans have flown it alongside banners reading “Love Football, Hate Racism.” At Pride marches, queer activists have reimagined it in rainbow hues. Arts events manager Cloe Gregson championed the ‘Everyone Welcome’ project, which aims to redesign St George flags and challenge the idea that Englishness must be white or monocultural. These acts contest the flag’s meaning in the public space; they don’t erase it. Reclamation here is about refusing to allow people to weaponise national identity.

And there’s plenty to reclaim. Englishness isn’t just empire and exclusion: it’s the Lionesses winning the UEFA Euros tournament in 2025, it’s ‘Sweet Caroline’ and ‘Mr Brightside’ belted out in pub gardens. It’s Bowie, Queen and The Beatles. It’s fish and chips, tea that solves everything, and the price of a Freddo that sparks national outrage. It’s Sunday roasts, National Trust walks, and pub quizzes where no one remembers who won but everyone remembers the argument over the capital of Canada.

These are shared traditions and culture that remind us of a true national identity, one that isn’t fixed or pure; it’s messy, borrowed, evolving, and that’s what makes it worth defending. We can still embrace the English flag, but do so whilst embracing its contradictions: a foreign saint, a borrowed flag, a culture built on other cultures.

Leave a comment