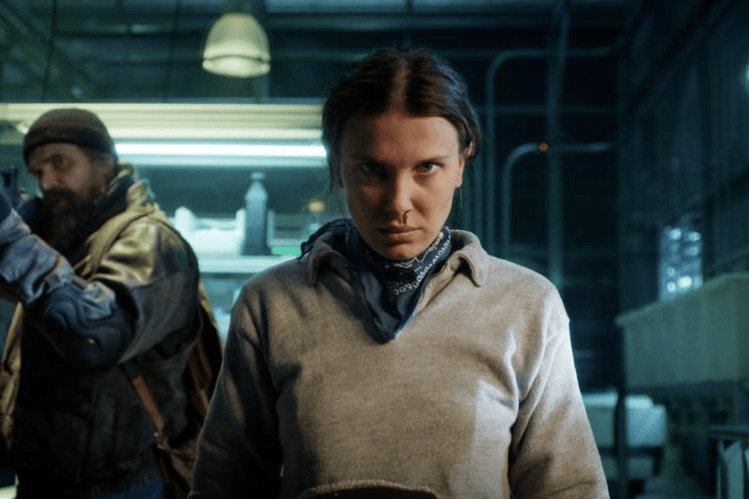

Image Credit: The Substance, 2025

When did cosmetic surgery become cool?

Gone are the days of the vapid film antagonist, the valley girl with her plastic alterations as the punch line. No longer is Meryl Streep’s choice to down the glowing potion of youth in Death Becomes Her (1992)so morally dubious, nor is the shameful surgical alibi of Brooke Windom in Legally Blonde (2001) shameful anymore. From tiktokers sharing their surgeons and what exactly to ask them for, to Anne Hathaway’s secret to staying 20 forever, getting ‘something done’ has gone from a shameful secret to an obvious choice.

As yet another layer of glamour is peeled back from the one percent, the desire (and ability) to attain the ‘perfect’ self has trickled down to the rest of us. Cosmetic surgery is no longer for fading soap opera stars, it’s for those who feel they look the most haggard – 18-25 year olds. One might not be surprised that the generation that grew up with Snapchat filters and unmonitored internet access has a strained relationship with theirappearance, but it’s not just about changing to fit the ideal form. Gen Z, more than a fear of the wrong nose or lip shape, is scared about something a bit more existential. An alarming amount of Gen Z is terrified of aging.

This is no news to the chronically online, or the frequent Sephora shopper. The target audience of the beauty industry has been slowly narrowing in on a younger and younger audience for decades. While Gen Z is too old for the Gen Alpha horrors of Sephora hauls, we are a generation who grew up immersed in algorithmic marketing, targeting us for beauty products way outside our age range In the years following that brief, euphoric period of left-wing cultural delusion that centered body positivity and self-acceptance, a form of social whiplash has brought us to a world obsessed with the ‘right’ aesthetic. Pretty Little Thing lost their Brat Summer sleaze to focus on polka dots and business wear, run clubs are overtaking THE club, and – worst of all – Gen Z is increasingly abandoning alcohol. While on the surface this return to a more wholesome, self-care focused culture may seem good, something lingers beneath it. Gen Z isn’t afraid of having unhealthy bodies – they’re afraid of having undesirable ones, those of a woman, not a girl.

Women have always been aware of the tentative connection between age and relevance. The eternal tale of the spurned, middle-aged woman being ignored for a younger, less talented woman is a cliché for a reason. But the age of relevance seems to be on a downward trajectory. When I first arrived at University, one of my flatmates looked at me, squinted, and said – “You’re like, 24, right?”. I still haven’t recovered – but why was I so offended? It was as if I had the priceless title of 19 stripped away from me, gone from the chic title of Girl, to the boring mundanity of Woman. No longer is the ‘It Girl’ in her mid-twenties, the Carrie Bradshaw-esque icon. The ‘It Girl’ is, reduced to its very definition, a girl.

Don’t worry, if you’re nearing that expiration date there is a solution. ‘Prejuvenation’, a trend observed by cosmetic surgeons as focused on preventative treatments for younger patients, is marketed towards Millennials and Gen Z. It involves getting Botox ‘before you have to’, and regular, smaller doses of filler to keep a more consistent picture. Research by the SUNY Downstate Medical Center shows that Millennials are more likely than any previous generation to get cosmetic procedures. A poll by ITV revealed that one in five 18-25 year olds have had cosmetic procedures done. While some dermatologists are expressing concerns about the relationship between an increasingly digital landscape and an uptake in clients, the so-called ‘Zoom-Boom’ has yet to halt. As always, the fears of women are a goldmine, and age has ceased to be a barrier. Cosmetic surgery is no longer focused on Kris Jenner’s miracle facelift, it’s for the young to look younger, with eternal girlhood as the end goal.

But what’s behind the need for girlhood, and who benefits from generations of women tied to transactions? To write off Gen Z’s obsession with youth as vanity is to ignore the root of the issue – the trend cycle that abandons anything no longer relevant, and the economic structures that reward it. The current cycle of social relevance forces individuals to constantly reinvent themselves to fit the theme of the day, turning their own existence into a product. The structure of fast fashion has imposed itself into the concept of womanhood, as our bodies act as the ultimate accessory to fit the current milieu.

This is not an issue inherent to Gen Z- they are just the first generation to not have experienced life without it. From those early, blurry snapchat filters that saved you from the reality of teenage appearance, to the automatic beauty filters on Zoom, does Gen Z really even know how to see their own reflection unaltered? Surveillance, especially in the U.K, is everywhere. It’s hard not to always be aware that something’s recording, to not look good for the cameras. The Molotov cocktail of algorithmic insecurity and social unrest can only be expected to light the fire of Gen Z’s need for social acceptance. No one is happier about this than big businesses. Insecurity equals profit. The beauty industry contributed £30.4 billion in 2024, making up 1.1 percent of the U.K’s total GDP. As costs of living rise, and costs of cosmetic procedures stay the same, the trade off seems more acceptable. Accessibility to cosmetic procedures, as well as successful marketing, removes fears and uncertainty over letting someone stick needles in your face. The eternal cycle continues, as brands create insecurities and then sell confidence back.

There is an urge, after all this negativity, to stand back with raised hands and go “not that there’s anything wrong with that!”. Is it really any of our business what women choose to do with their bodies? Influencers are praised for their authenticity when speaking about their modifications, and echoing in the comments is one familiar sentiment – “You’re not ugly, you’re just poor”. But that raises another question: what is ugly? If Gen Z is so terrified of aging, of the social irrelevance and looming responsibilities of being ‘old’, then I wonder why we choose to root our perception of beauty in such unstable waters. The Kardashians have supposedly removed their implants, Pamela Anderson no longer wears make-up, and ‘natural’ beauty is in. In Generation Z’s race for eternal girlhood, forever existing in that sweet spot between annoying and boring, I fear we may be erasing ourselves for something that will change before the filler is healed.

Leave a comment