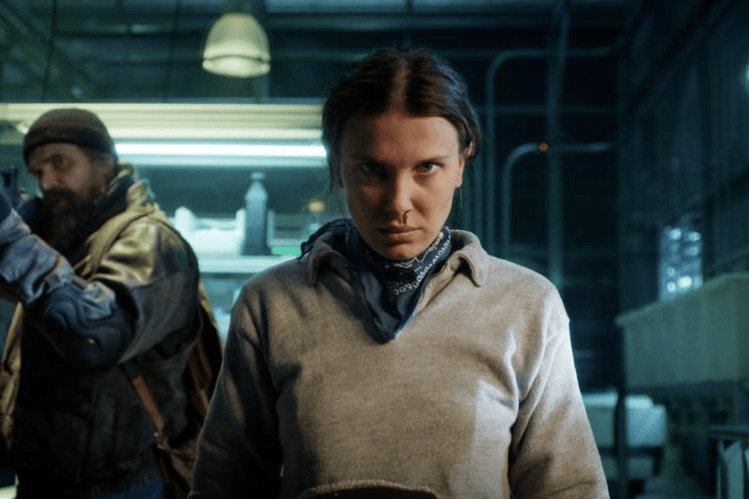

Image Credit: Tim Hermans

Content Warning: mentions of eating disorders and weight loss

The good old 90s and 00s – the days where partying, socialising, and shenanigans reigned supreme. Icons like Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie were photographed in clubs and bars, promoting a socialite lifestyle. Anyone who was anyone was hitting the town on a Saturday night. The idea of a fun, messy night out ending with a takeaway and a good story rang idyllic in the ears of youths all over the country. But not anymore.

Health and wellness have taken over pop-culture. Sunday morning pilates and the ‘Clean Girl Aesthetic’ have replaced Saturday night clubbing and ‘Ladette’ culture. Influencers and celebrity icons alike have moved away from alcohol and nightlife, replacing them with refined appearances at iconic venues such as London Fashion Week, and taking on sponsors from supplement, sportswear, and skincare companies. The youth and young adults of today are increasingly focused on health and wellness in its many different forms. Whilst this is typically considered to be a focus on the gym, there is a growing interest in meditation, yoga, and journaling. Is this truly a step away from drinking and a movement towards health, or is it a variation of the diet culture that characterised previous decades?

Margaret Thatcher was forced to resign in 1990, and the British population experienced two successive Labour victories from 1997 to 2010. Ladette culture, a social phenomenon where young women in the 90s and 00s engaged in traditionally masculine behaviours such as heavy drinking, smoking, and swearing, subsequently grew in popularity, An expression of feminism and female rebellion to some, Ladette culture meant that more women entered the male dominated spaces of pubs, clubs, and bars, and generally behaved in an ‘unladylike’ manner, often being accused of acting as badly as the lads. They refused to be bound by their gender and gender roles. Moreover, women in this era had greater opportunities for career progression than ever before, and therefore more money and ability to go out and engage in this form of cultural rebellion. Women had gained both the ability and the stability to engage with nightlife in a way they had never been able to before. This led to an entire generation of youths with social lives centred around drinking, clubbing, and socialising, instead of just the social lives of men.

The ‘Clean Girl Aesthetic’ very much juxtaposes the Ladettes. It promotes a minimalist, polished style, with neutral tones and a ‘put-together’ look. The fashion inherently favours smaller, white bodies and is notably feminine in its presentation. Engaging with pilates, yoga, ‘clean’ eating and a generally active lifestyle is a key part of the Clean Girl Aesthetic. The ‘Clean Girl’ exists at a time of rising conservatism, growing global intolerance, and an undeniable cost of living crisis, where many are forced to choose between using the heating, eating, and paying rent. These two archetypes of women are incredibly different, even down to the contexts in which they exist(ed). The Ladettes seemed to have much more fun than the ‘Clean Girls’, with the latter seeming to take itself much more seriously and having no time for shenanigans. However, it would be incredibly naive to say that they are not deeply intertwined.

It is true that the COVID-19 pandemic changed much of British culture. Remnants of the era continue to haunt public spaces; bus stops with socially distanced feet sprayed onto the ground and stickers reminding us all to keep a two metre distance have become a forgotten yet omnipresent memento from when society stood still. The social separation, ‘bubbles’ and ‘rule of six’ forced the population to be deliberate and intentional about socialising with loved ones in a way which had never been seen before. Many took up hobbies such as baking, gardening, and running with their newfound time and energy, working from home came into the popular consciousness, and a complete re-evaluation of which workers were necessary for the function of society. It was a time when the natural order had been completely turned upon its head.

Self-improvement and fitness very quickly became themes of the pandemic. Fitness influencer Chloe Ting shot to fame and popularity with her famously short, high-intensity fitness routines. She created challenges on her website with her free and easy to access YouTube videos, ranging from two to eight weeks long. Many participated in these challenges, with some filming videos of their progress, including before and after photos. Many of these people were middle-aged women, often mothers, looking for a way to exercise that would fit into their days and wanting to do something for themselves. Many of these women will have participated in the 90s and 00s social culture.

Chloe Ting’s fitness content alone is not problematic. She provides a free fitness resource that many have used, enjoyed, and learned from. However, as with much fitness content, its position in the context of a society that promotes smallness and thinness often leads to the perpetuation of diet culture and self-loathing. Many,particularly women and girls, used content such as Chloe Ting’s over the course of the pandemic to ‘glow-up’ – to become ‘sexy’ and ‘hot’, so that, post-pandemic, they will look like a completely different, ‘better’, skinnier person. Social media became a hotbed of before and after pictures, fitness updates, ‘Government sanctioned exercise’ jokes, and ‘body-checks’. This has grown, developing to the point where now, in 2025, fitness influencers are able to make a living recording themselves doing workouts and eating 30 grams of protein with every meal. The conflation of fitness, thinness, and health, did not stop at the end of the lockdown.

The British public, like much of Western society, is entrenched in diet culture. EBSCO defines diet culture as “a societal belief system that prioritises thinness and appearance over health and wellbeing. It promotes practices such as calorie restriction, adherence to fad diets, and the labelling of food as good or bad”. The diet culture of the 00s included expectations that women ate nothing, had tiny bodies, and were perpetually an elegant, feminine presence. This has rapidly transformed into posting your kilometre running splits on Strava, forcing 30 grams of protein into every meal, hitting all of your macros, and closing all of the rings on your Apple Watch.

The Ladettes did not escape diet culture or media surveillance. They faced intense media backlash which questioned and critiqued their femininity. This backlash was so severe that Ladette to Lady was created; a television program in which young women were taught and essentially bullied into becoming “proper” ladies. Alongside this, female bodies were being blasted in major publications at all times. One such headline is in regards to Britney Spears’ comeback performance at the VMAs in September 2007. The New York Post published the headline: “Lard and Clear”, with E! Online claiming that “That bulging belly she was flaunting was SO not hot,”. This intense media scrutiny of female bodies extended beyond celebrities and to the Ladettes, leading to many developing body image issues, eating disorders, and food struggles that have gone on to last for the entirety of their adult lives.

Modern diet culture can be considered a rebranding of the same diet culture that women faced in the 90s, 00s, and before. Fad diets and misconceptions about food still remain, and the emergence of weight-loss drugs like Ozempic have intensified the moralisation of losing weight, creating a ‘good’ way and a ‘lazy’ way to lose weight. Eating clean and organically is a necessity, and trends such as ‘75 Soft’ and ‘75 Hard’ entangle self-improvement and diet culture into one trendy entity.

The Ladette and the Clean Girl, whilst very different in their appearances and behaviours, are firmly tied together by the culture promoting restriction and skinniness as peak femininity; the goal to which we should all be oriented. Both engage with feminist rebellions in different ways, meaningful within the context of their era.

Whilst the Clean Girl identity is not an inherently feminist expression itself, the massive rise of women’s sports and fitness around the time this aesthetic flourished means that more women are increasingly unafraid to engage in what is typically perceived as the most masculine activity – the gym and weightlifting. Traditionally, women are expected to prioritise cardio, weight loss, and maintaining a slender appearance. By engaging with weightlifting and focusing on strength, women are rebelling against what it is expected for their bodies to look like. Moreover, these women are entering a traditionally masculine space in both competitive and non-competitive ways, akin to the way the Ladettes entered traditionally masculine spaces like pubs, clubs, and bars.

Ladette culture and the Clean Girl Aesthetic are incredibly intertwined despite their incredibly different attitudes, antics, and expressions, and can be considered two sides of the same coin. Both deeply resemble the societies in which they are situated, expressing individuality differently and pushing the boundaries placed upon them by the patriarchy. Whilst Ladettes are seen to be having more fun, they also faced an intensity of media scrutiny that other generations have not suffered. The Clean Girl Aesthetic, whilst not deeply criticised in the mainstream media, exists in a time of great intolerance and misogynistic upheaval. Women across generations are fundamentally connected by good and bad, and undeniably by the impossible expectations placed upon them by diet culture.

Leave a comment