Image Credit: Tilda Harrison

The works of Jane Austen have always been profoundly appreciated and celebrated, such as with the Austen Turner exhibition at Harewood House which I was lucky enough to visit in October. But doesn’t it seem that recently our connection to Austen’s novels are becoming more distant? Through half-heartedly modernised Netflix adaptations and new tone-deaf cover designs, there seems to be a conscious effort to change these beloved novels to the point of tricking audiences and readers into enjoying them.

Following my friend’s recommendation when I was younger, I watched Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice (2005), which quickly became one of my favourite films. Thankfully, my first experience of Austen’s work was through this authentic retelling, and I fell completely in love with her beautifully complex women and their stories. I’m not ashamed to admit that watching the film adaptation of the novel inspired me to read it, and actually helped my 14-year-old-self understand the complexities of the language that had so often felt inaccessible to me.

Acknowledging, then, that Austen’s language and style can feel difficult to modern readers is one of the first steps we must take when trying to encourage new generations to read classics. However, I feel that in recent years, classic novels are being adapted and intentionally ‘dumbed down’ almost to the point of insulting their audiences’ intelligence. Unfortunately here, we do have to judge books by their covers; Penguin Books recently re-released Austen’s novels in their ‘First Impressions’ collection, which were widely criticised for prioritising appealing to modern readers through their book covers, and purposefully misrepresenting the tone. It seems to suggest that Austen’s novels blend into the current modern romance novel market, which somewhat undermines readers’ intelligence by attempting to minimise the difficulty of the intricate language used by Austen. If I had read Pride and Prejudice at 14, having felt it was being marketed to me as an easy-to-read romance (as the colourful and heavily stylised covers suggest), I probably would have given up, feeling too overwhelmed by the deceptively tricky language concealed by the marketing. Part of the enjoyment of these classics is being transported to another time and place, not just through the story, but through the 200-year-old style.

I want to say here that I do not disagree with modernisation and increased accessibility of classic literature (who doesn’t love Clueless (1995)?) and some aestheticised versions of the novels can be incredibly beneficial. For example, around the same time as the huge success of the first series of Bridgerton, Autumne de Wilde’s Emma (2020) was released to high praise from audiences and critics alike. Though a somewhat stylised version of what regency era Britain entailed (though not to the same scale of modernisation and stylisation as Bridgerton), the film did not take away from the original substance or tone of the novel and perfectly managed to balance the romance, social commentary and playfulness of Jane Austen that I fear we are seeing less and less of.

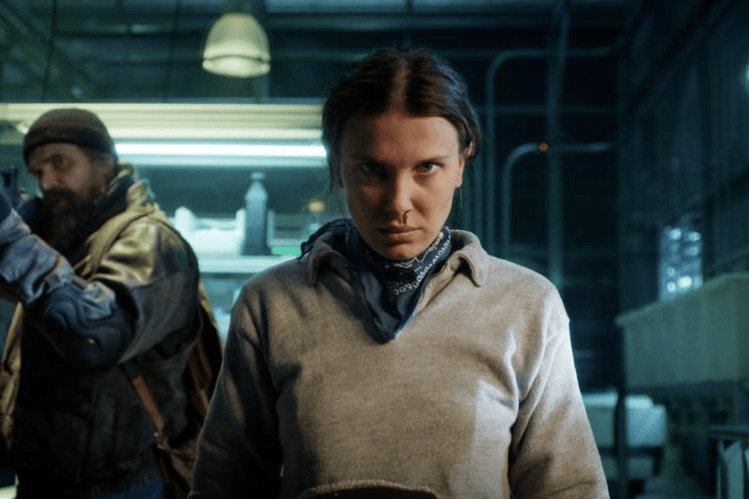

However, as increasing numbers of tone-deaf modernisations of the novels continue to be released, I feel that we need to be careful of our connection to them being lost. An example that springs to mind is Netflix’s Persuasion (2022) which appears to completely misread (or ignore) the original tones of Austen’s novel that centres on Anne Elliot’s heartbreak over her continuing love for Wentworth. Instead, Dakota Johnson’s version of the character continually cracks jokes and breaks the fourth wall in a weak imitation of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag (2016). With lines such as “he is a ten, and I never trust a ten” and “we’re worse than friends, we’re exes”, Persuasion clearly attempts to bridge the gap between modern audiences and fans of classic literature but instead refutes our intelligence and understanding – the film holds its audience’s hands through the plotline and not-so-subtle jokes, a direct contrast to the faith Austen so readily placed in her readers’ abilities to understand her subtle humour and irony.

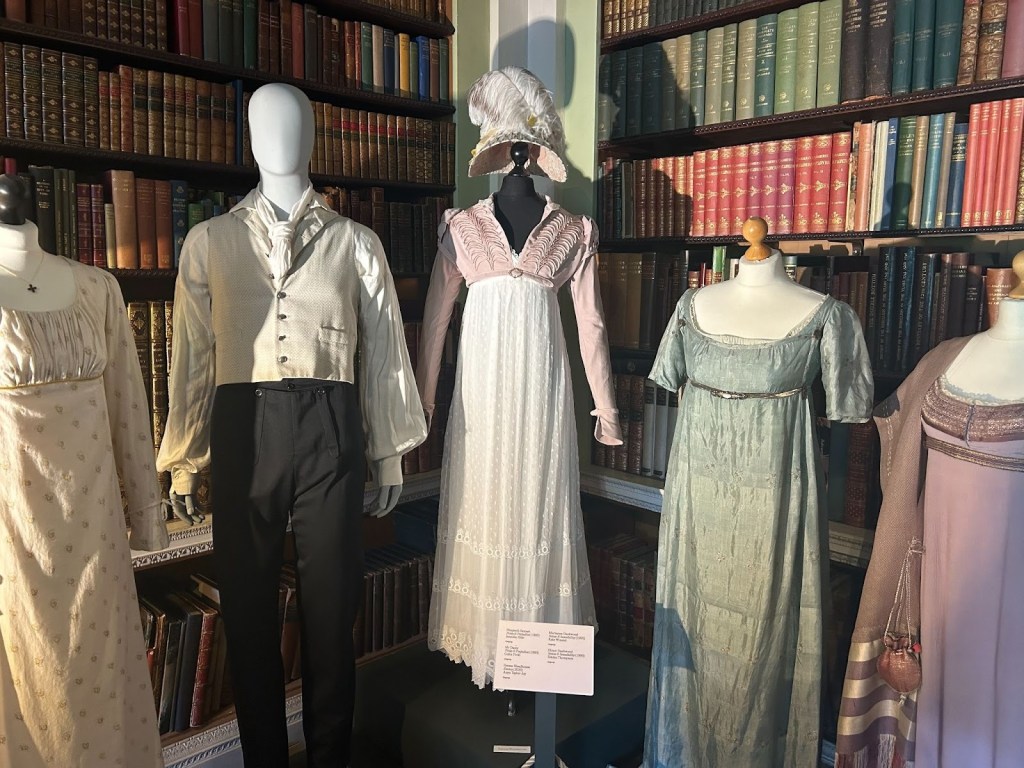

It seems strange to me that producers feel the need to alter the novels when faithful adaptations are so readily celebrated. A recent Harewood House exhibition on Austen featured one of the many dresses worn by Anya Taylor-Joy in her titular role in Emma, alongside Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth’s outfits from the BBC’s Pride and Prejudice (1995),as well as Kate Winslet and Emma Thompson’s dresses from Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility (1995). In the short time that I was there, crowds of people were gathering around these costumes, adoring the intricacy of the designs and the actors who had worn them; it struck me how much people have and still do adore the adaptations of Austen’s work which are authentic and respect her novels, even years after their release.

What really excited me, though, was the complete range of people who were there. One group was made up of an elderly couple who were taking their granddaughter around and who, at a very young age, seemed to be familiar with Elizabeth Bennett and Mr Darcy. She recognised the poster of Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice (2005) and delighted in seeing the costumes. I doubt this young girl had read Pride and Prejudice herself at such a young age, but in the same way I did, she had become familiar with Austen’s novels and fallen in love with her work through watching a faithful, authentic adaptation.

This is hopeful, and despite publishers and producers attempting to appeal to new audiences through tricking them with the covers or the modernised humour, it showed me that there are audiences who want to celebrate Austen’s work without the aestheticisation. Why can’t we accept that certain novels and literature can be kept authentic and safe from modernisation? With the declining popularity of reading amongst young people, isn’t it important that they don’t feel tricked by deceivingly colourful and modernised covers of books? Especially with new adaptations of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice (which appear to be authentic retellings) set to be released over the next year, this is perhaps a new generation’s gateway into Austen, rather than the aestheticised book covers. It is my feeling that audiences are more than happy to fully indulge and immerse themselves in period dramas and novels, shown by continuous celebrations and re-releases of Austen and her work. Whether these are the new and faithful adaptations, or exhibitions like the one at Harewood, they continue to engage and inspire hordes of people. So try out reading that classic and persevere- you never know, it could become a favourite!

Leave a reply to Eleanor Lilley Cancel reply